How much is too much? It’s difficult to say when you look at Oliviero Toscani’s photographs for Benetton, which feature anti-racist messages as well as portraits of convicted murderers. Death, sexuality, migration – the master of provocation has never shied away from taboo subjects. He was “woke” before it became a controversial term – and garnered criticism and admiration in equal measure. The first comprehensive retrospective of his work can now be seen at the Museum für Gestaltung in Zurich .

We open social media every day and allow ourselves to be swallowed up by the maelstrom of scrolling. Between the self-portrayal and the inspiring quotes, we also come across the atrocities that happen in the world. The highly polished selfies are then joined by images of war dead – and our brains have to categorize and process everything in a matter of seconds. Even the meticulous curation of our own algorithm does not protect us from grotesque news. A few concerned voices occasionally throw the word desensitization into the mix, but there isn’t much of an outcry – or we are all very good at banishing the obvious grievances to the farthest, darkest corner of our emotional world. If headlines and horrific images hardly affect us any more, then even an advertising poster with a shock message leaves us cold, doesn’t it?

Between hedonism and social criticism

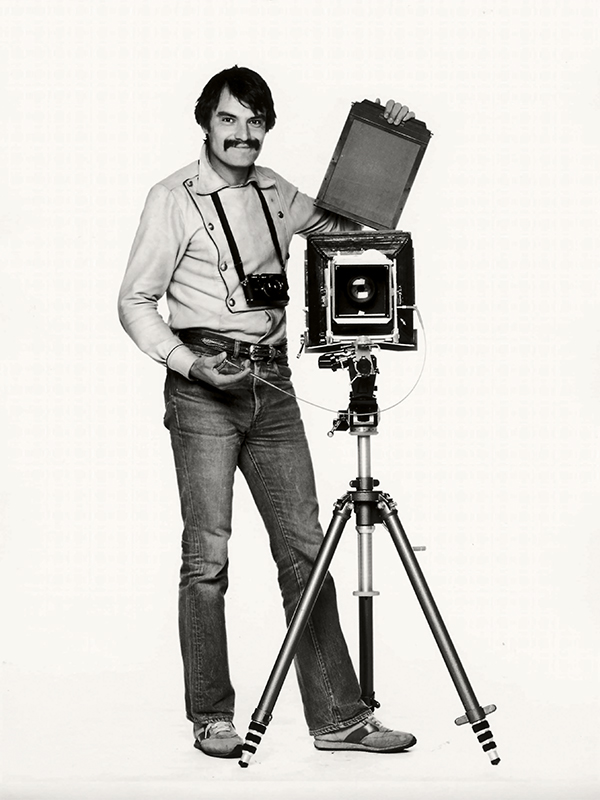

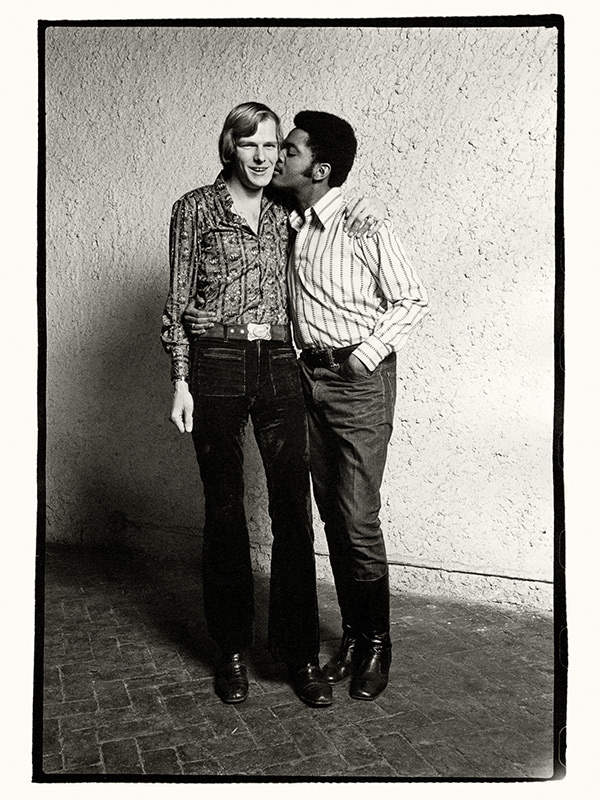

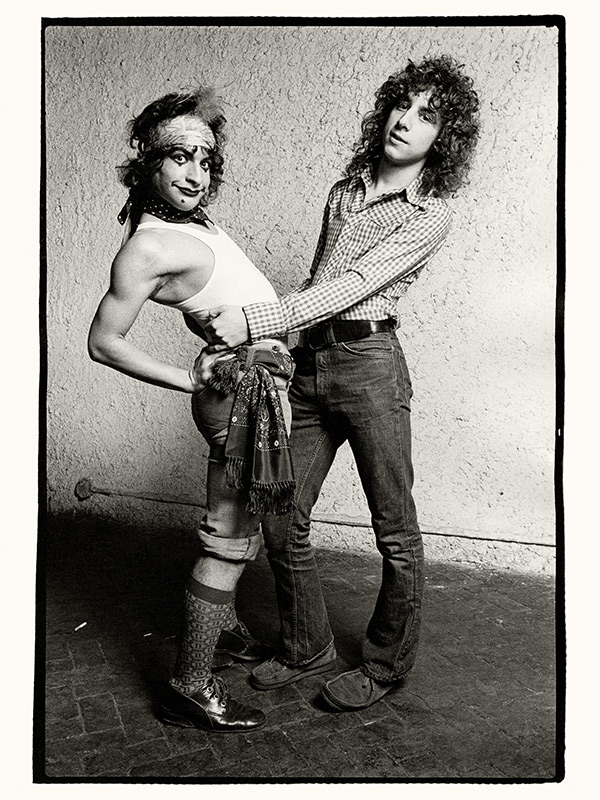

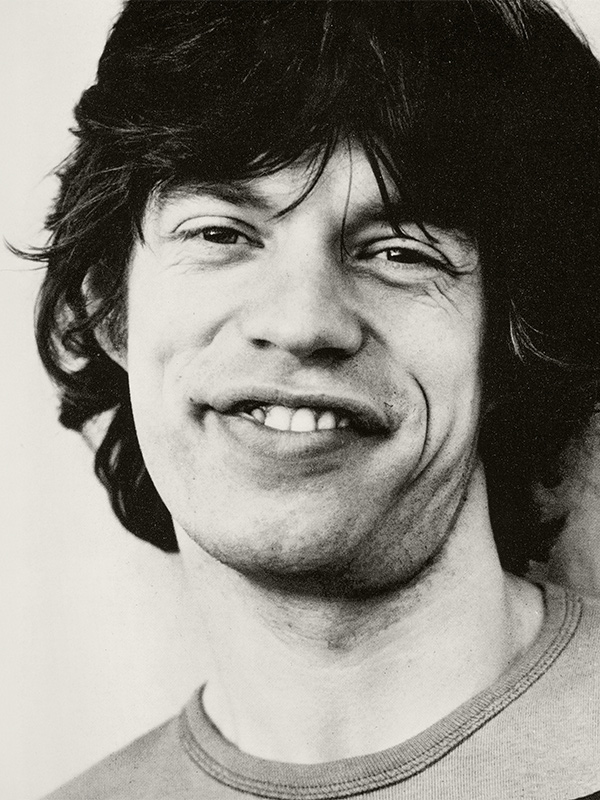

Oliviero Toscani proved for decades that advertising, the fashion industry and social grievances were once a dream team for artists who wanted a reaction from the public. He brought together what did not really belong together. But let’s start at the beginning: in 1961, Toscani joined the photography class at the Zurich School of Applied Arts (now Zurich University of the Arts). While still a student, he won a competition and was flown to New York. He worked on his first fashion shoots and at the same time immersed himself in the street photography scene. The Italian was particularly taken with the black community and the wild party culture: he photographed eccentric partygoers in the legendary New York clubs Limelight and Studio 54 and took portraits of black Americans. And he became friends with none other than Andy Warhol, whom he also repeatedly staged in front of his camera.

While racism, wokeness and identity politics are hotly debated in the media these days as if they were brand new 21st century topics, Toscani has always simply acted. century, Toscani has always acted simply. In 1972, he convinced L’Uomo Vogue to exclusively feature people of color in a magazine. He succeeded because he submitted his material too late and the magazine had no other choice. Toscani was “woke” in his own way, before the term was discussed to death and emptied of any meaning. Racism, migration, gender identity – today’s hot topics have always interested Toscani. Sexually liberated people were a popular subject for him, as were exploitation, child labor and illness. Hedonism and social criticism go hand in hand in Toscani’s work.

In a radicalization frenzy

1982 marks the beginning of Toscani’s Benetton era. The beginnings are almost well-behaved, as Benetton clothing can still be seen in the campaigns. However, it soon became clear that Toscani wanted to do more with the brand than just advertise fashion. From 1989, the Benetton campaigns no longer featured any fashion at all. A naked black woman breastfeeding a white baby, a priest and a nun in an intimate kiss: provocation has long been Toscani’s middle name. His campaigns are a means of bringing issues to the attention of society that are otherwise not reported on. In this way, fashion and the subject become increasingly distant from the camera. The bloodstained clothing of a fallen soldier from the Bosnian war, the anorexic model Isabelle Caro, who died a few years after the photo was taken, exploited children at work: is this still advertising at all? And if so, for what?

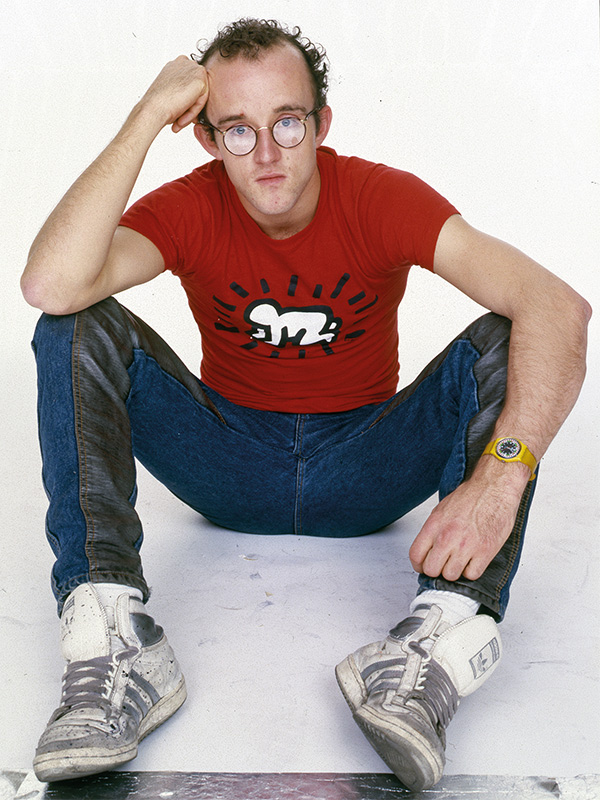

Toscani’s motto seems to be that there is more to it. He deals with the fact that nobody talks about Aids in a Benetton poster showing a dying Aids patient and his family. This also attracts criticism, but in the end Toscani makes a remarkable contribution to raising awareness of Aids. His own Benetton magazine “Colors” dedicates an issue to the subject, and the aim is not to shock, but to educate people about how they can protect themselves against the disease.

To the limit and beyond

But is it okay to depict people who are dying on a fashion house’s advertising poster? Or working children who don’t even know that they can be seen on posters all over the world? Is there a boundary between advertising and fashion photography, art and social enlightenment? Not for Toscani, and so he is repeatedly accused of instrumentalizing social problems and the fates of individual people for advertising purposes. For Toscani, there never seemed to be any limits. For Benetton there are. After Toscani photographed inmates sentenced to death for a campaign in 2000, Luciano Benetton parted company with him in a dispute. The resentment of the victims’ relatives was too great for Benetton to justify the campaign in any way. But here, too, Toscani blurs the boundaries by photographing people who have been wrongly convicted and thus actually take on the role of victim rather than perpetrator. And yet: seeing a murderer on a poster is a step too far for many.

Today, one wonders: where are Toscani’s successors? Are we really all so desensitized that advertising campaigns have lost their scandalous magic, or has no one – neither photographers nor brands – ever dared to dig into the abysses of humanity and show the public the grotesque? What do we do with images that don’t make us think, that leave us cold? We forget them. And that is the very last thing you want as an artist.

Photography and provocation

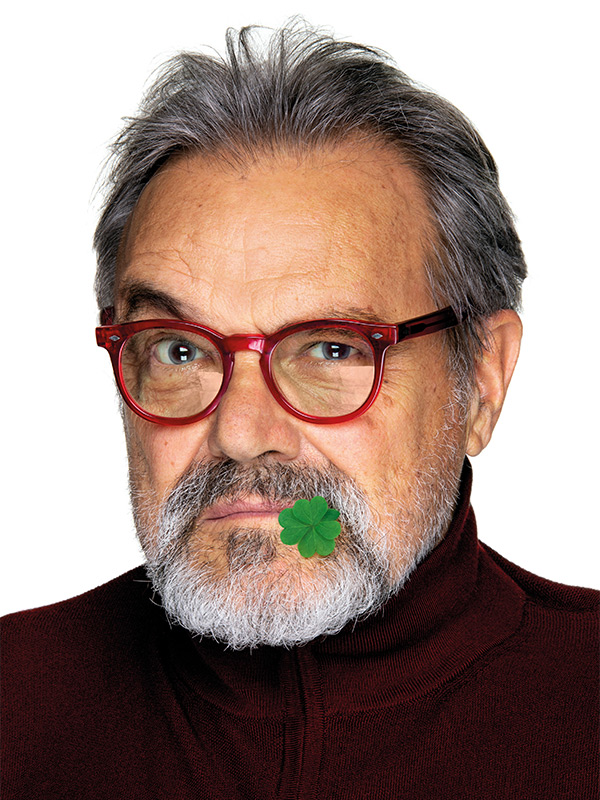

Provocation! Nudity! And all sensitive topics from racism to AIDS: there is hardly anything controversial that Oliviero Toscani has not addressed in his photography. The Museum für Gestaltung Zürich is showing the first comprehensive retrospective of his work and taking the scandalous photographer back to where his journey began: The now 82-year-old was in the photography class at what is now the Zurich University of the Arts from 1961. The exhibition includes over 500 pictures – from his beginnings in New York to the provocative Benetton campaigns and his numerous portraits of people from all over the world.

Oliviero Toscani:

Photography and Provocation,

Museum für Gestaltung Zürich Ausstellungsstrasse 60, 8005 Zürich

April 12 to September 15, 2024

September 2024

www.museum-gestaltung.ch

Want to experience provocation up close? Then let’s go to the Museum für Gestaltung in Zurich!

We also think the pictures for our interview with fashion photographer Lucia Giacani are stunning.

Photos: Oliviero Toscani / Museum für Gestaltung Zurich