Contaminated soil. Poisoned people. Overproduction. And somewhere, people in suits are raking in millions with cheap fashion, produced on the backs of those who can’t help themselves. Elizaveta Fateeva knows the abysses of the fashion industry, having worked for Jil Sander and Lanvin herself for many years. Now the Vienna-based Russian is doing everything better with her own label Fateeva, tailoring fashion from leftover fabrics that is more than just clothing – it is a declaration of war on the prevailing status quo.

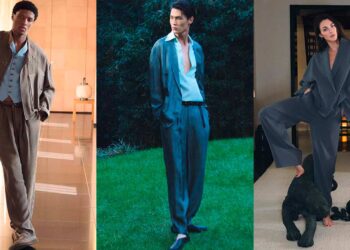

Photos: Lisa Edi, Stefanie Moshammer, Tatyana Vlasova

FACES: You have worked for major fashion labels. How did you come to this?

Elizaveta Fateeva: I studied fashion at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. Raf Simons was a professor at the time – I also did an almost two-year internship with him in Antwerp during my studies and was the first assistant to his right-hand man Pieter Mulier. During my studies at the Angewandte, in addition to fashion design, I also did many collaborations with architecture and industrial design students, where we developed shoes together for my collections. Pieter hired me as an assistant for shoes and accessories and, after I graduated, brought me to Jil Sander in Milan as a junior designer for women’s and men’s shoes, where Raf Simons had already been creative director for several years. A year later came the offer from Lanvin.

F: Jil Sander, Raf Simons and Lanvin were among your employers. How do you imagine working for such a large label?

EF: Raf Simons was an incredibly enlightening experience for me. The team was very small back then; I was allowed and had to do a lot and was involved in many processes. At Jil Sander, I was given a completely different responsibility for the collections and the design, and in addition to design, I also helped a lot in development and production. Back then, I spent a lot of time in the factory in Venice, where I was able to learn a lot on site. Although I had never made a shoe with my own hands before, I knew every single step of the process because I was allowed to work with the technicians in the factory the whole time and was able to realize designs directly on site. After twelve months working as a junior designer at Jil Sander, Lucas Ossendrijver brought me to Lanvin in Paris as head designer for men’s shoes. It was completely new waters – as if I had skipped secondary school and gone straight to university. Learning to hold everything together as a Head Designer in a large team and not get lost was very difficult at the beginning, but in the end it worked out precisely because little experience also offered a lot of room for experimentation. I ended up working for Lanvin for seven years, it was a wonderful time in a wonderful team.

F: There are many small steps before the actual presentation on the catwalk. What did they look like?

EF: Each collection started with input from the creative director, then we did research, prepared our own presentations and visions and visited trade fairs to look for new materials and techniques. Then we created new lasts, soles and the first prototypes. The show collections offered more room for experimentation, the commercial part was more reduced and wearable. I spent most of my time between Portugal, Spain and Italy. When working with shoes, rules and exceptions alternate – that’s exactly what I love. A shoe is the result of parts from 15 to 20 different producers. Imagine the last, lining, sole, insole, eyelets, laces, leather, mesh and so on. Every component of a shoe has to be researched, created and developed.

F: What is the best story from your years at Jil Sander and Co?

EF: When I was head designer for men’s shoes at Lanvin, I wrote “Pharrell You Rock!!!” in silver pen on the insole of a sample for Pharrell Williams. (laughs) Before the Lanvin fashion shows, we were often visited backstage by stars who later sat on the front row. I often crawled around the models on all fours and checked the shoes, which I also cleaned and polished from time to time. Every now and then I also caught the shoes of actors and actresses, which amused them to no end. I also once told an actor to please stand in the line-up of models. I am very strict!

F: You’ve seen these very nice documentaries about the tailors at Chanel on Rue Cambon in Paris. Is this really what goes on behind the scenes at big brands?

EF: Loïc Prigent’s documentaries were actually very pretty and nice; they also came out at the time when I was still studying. My favorite fashion documentary is still the 1995 documentary “Unzipped” about Isaac Mizrahi, where everything was a bit rougher and you could see the difference between a functioning fashion house with a big name and a small label with a small budget trying to build something with the support of friends.

“I’m an outsider and a nerd and spend most of my time in front of the sewing machine.”

F: Why did you decide not to work for such labels anymore?

EF: After seven years at Lanvin, I have spent much less time in the office in Paris than I did at the beginning. At the time, I was commuting 50/50 between Vienna and Paris and was looking for a new challenge. At Lanvin it was almost too cozy for me at some point. At the same time, I started working for Ferragamo in Florence, so I was on the plane six to seven times a week. Sometimes I didn’t even know where I was at night. This resulted in two burnouts. On the one hand, I didn’t want to carry on like this because I simply realized that I wasn’t getting anything together and the pressure was getting bigger and bigger. On the other hand, after this long time in the industry, I’ve seen behind the system and I didn’t like what I saw. While I was working for others, I started to build something of my own. I needed this as a retreat. That’s how I came to found FATEEVA in 2017.

F: How much respect did you have for starting your own fashion label?

EF: I didn’t realize it like that at the beginning. I took a year to develop my own models before I even launched my label or told anyone about it. It wasn’t until I felt that everything felt right that I knew I was ready to do it! The most important thing was to tackle one thing at a time. When I founded the company in 2017, I couldn’t even imagine that knitwear would be added later and that I would be sitting at a sewing machine and sewing clothes again in lockdown in 2020 after 15 years. The timing was right. The idea of working with overproduced materials did not come immediately either. It took some time for everything to find its place. I’m glad that I failed so often – because that’s exactly what inspired me to break new ground.

F: You have your pieces produced in a tailor’s shop in Riga. Why there in particular?

EF: I grew up in Riga after my father and mother decided to leave Russia when I was five years old. I moved to Vienna when I was 17, where I did an apprenticeship as a tailor. During my studies, as the collections got bigger and bigger, I looked for production facilities. I met Aiga during a visit to my father in Riga – we have been working together for 18 years now. She’s just as much of a nerd as I am, and we try to challenge each other every time. In recent years, I have never met anyone else who approaches things with such perfection and is not afraid of new challenges. Through Aiga I also became aware of other tailors and a larger production in Riga who understand the complexity of working with overproduced materials and appreciate quality. I’ve been living in Riga again for two years now and always stay there for the development and production processes.

F: Is a 100 percent transparent value chain even feasible for a fashion label?

EF: After twelve years of experience in the big fashion houses, which have a very different approach to creative work, development and production, I realized that it is not possible for such a fashion company to create complete transparency. I was hoping that the pandemic would change that… Many young labels have the opportunity to work transparently from the outset and from the ground up, creating a sustainable foundation. They find new ways in production, look for sustainable alternatives and remain creative at the same time.

F: You use material from overproduction. How do you get hold of this?

EF: My brother has been living in Italy for 25 years in a small town in Emilia-Romagna, where there are a lot of productions. I then found out about the remaining buyers through his wife. All clothing factories receive the orders for production from the fashion labels and have to order the materials from the manufacturers themselves. The prices depend largely on the quantity ordered. It can therefore be cheaper to order more than to pay a surcharge because you do not reach the minimum production quantity. In principle, you always order more if errors occur during production or if part of the material is faulty. This is the reason why so much material is left over from production, which is not reused but stored and eats up so much money. So-called remnant buyers then buy up this material and sell it in smaller quantities. I have discovered four of these remaining buyers over the past 16 years, with whom I work regularly. Visiting them is always an adventure from which I expect everything and nothing. I then search for a long time and spend a lot of time trying to find the right parts because these places are often very disorganized. You can’t have any idea what you’re looking for, otherwise you’ll never find it. I always go there with an empty head. I usually use the materials, fabrics and accessories I find as a source of inspiration or a point of reference for my collections or ideas.

F: Is it difficult for you as a designer to design with sustainability in mind? Do you feel restricted?

EF: It’s precisely these kinds of restrictions that inspire me. When you work within these boundaries, completely new ideas emerge. You experiment with materials, look for new techniques and processing methods and become a kind of product designer. When I look back, I find it much easier to work the way I do today.

F: You only produce in small quantities. Why are you doing this, and is it even economically feasible?

EF: My production always depends on the amount of materials I find. This is not a jackpot for the productions, for whom it would be much more convenient to produce 100 identical shirts in the same color in the same size. In Latvia, I am working with my seamstress Aiga on preparations for small productions in which more than three to four pieces can be produced. We usually cut everything together directly in the factory, because the fabrics often have different widths and behave differently, so you have to be on site to find solutions. The production price is much higher than for a large production, but this aspect is also very important to me. I never negotiate production prices, mutual respect comes first for me – I know that the factory makes a big exception for me. It is a very strong team that I depend on a lot and vice versa, we have already worked together on many collections. The team is irreplaceable. I know that they all have to be happy for me to be happy. I walk her dogs, we cook and drink coffee together, I always get fresh vegetables from Aiga’s garden, and we think together about what we can do better or differently in the future. Last year, Aiga and I had a serious car accident because she was driving too fast on the snowy road in Jurmala, a suburb of Riga. She was under so much pressure because she really wanted to finish the work before I flew back to Vienna. Fortunately, nothing bad happened – but we promised ourselves after this incident that we wouldn’t allow such stress to happen again. That was a very important sign.

F: How do you convince consumers of your label who normally shop at Zara or even order from Shein?

EF: I don’t think my customers shop at Shein and Zara. This statement is by no means intended to come across as arrogant. But it takes a certain amount of conviction, research and interest to buy something from me. I would never be able to convince a consumer who normally shops at fast fashion brands to buy an upcycled cashmere sweater from FATEEVA for 400 euros that will last a lifetime, instead of buying 20 pieces from Shein or Zara for the same money. Trends and shopping mania dominate the fashion world far too much for that. Fast fashion labels have huge budgets to convince customers that what they do is good – even if a piece costs just ten euros. These labels offer no transparency, no one can look behind the scenes. You simply take an influencer with ten million followers as a campaign model or, even better, as an ambassador and address their followers as new customers. Another problem is buyer behavior: People are more likely to spend 20 euros twice and ten times in three months than 400 euros once.

F: How do fellow designers react to your business model?

EF: I get a lot of advice that, funnily enough, has nothing to do with what I do and what I stand for. I’m an outsider and a nerd and spend most of my time in front of the sewing machine, in the factories or at my tailor’s in Latvia, where I also get very little of the glittering fashion world. To be honest, I’m very happy about that.

F: How did you feel about the fashion industry in the past, and how do you feel about the industry today?

EF: When I was in Paris for the first time, it was like a dream come true. Everything has been romanticized. The more and longer I worked in fashion, the greater the pressure became. I have tried to develop a protective mechanism to protect myself from overwork. I created six collections a year for Jil Sander and four for Lanvin. When you are constantly reaching your capacity and have no energy, you realize how sensitive you are and what happens when you suddenly can’t do anything anymore. I had two burnouts in just one year, was on an airplane six times a week and sometimes didn’t even know where I was anymore. You can no longer be creative if it’s all about getting from A to B and C all the time. At some point, this way of working sucked everything out of me. After that, I thought long and hard about whether I really wanted to be part of this world again.

F: Can fashion ever be sustainable?

EF: For sure, but you also have to do something about it. There are many important voices and a large community of ambassadors, organizations or writers who are not only concerned with the sustainability of fashion, but also with gender, race appropriation, climate change, the circular economy and labour rights. It’s all connected. However, I have the feeling that large companies or fashion houses that want to make a profit focus on the exact opposite. In some cases, it’s not even about creativity, but about sales figures. Ten years ago, 70 percent of all the collections I worked on consisted of carry-over models – models that already existed and that you knew would sell well. At some point, I was only dealing with marketing people who dictated to me what I should design and what the collections should look like. It’s scary to see what fast fashion has done in the past decade and how blindly and ignorantly most people deal with it. Even during the pandemic, when there was finally time to sit down together and find ways to do things better, many people simply wanted to bridge the gap and then carry on as before.

F: Which materials or production steps are particularly difficult if you want to produce sustainably?

EF: In order to produce sustainably, you have to go back to our consumer behavior on the one hand and look at the origin of the product on the other. The creation of the material is particularly important, as its production often remains hidden. Our consumer behavior has turned the entire industry upside down in recent decades – according to various sources, 100 to 150 trillion new items of clothing are produced every year. Cotton fields are treated with pesticides, chemicals are used to speed up the processes, and the earth has no time to regenerate. In China, Taiwan and Bangladesh, man-made fibers such as polyester are mixed with chemicals during production with dyes, all of which flows into the rivers and through the cities where people live. What is all this for? So that Zara and Shein can fill their shelves every week with new products for ten euros, which are worn three to five times after purchase and then end up in the bin again.

Every production step is harmful if it is based on our current consumer behavior. There is so much material that has already been produced. Do you just throw it away or do you make something out of it? I find it more sustainable to work with overproduced and already existing leather than to pollute rivers in Asia so that a lot of water is used in processes and tons of chemicals come into play to produce so-called “vegan” leather for new collections.

“At some point, I was almost too comfortable at Lanvin.”

F: How should we consume fashion today?

EF: The question is: What do we actually need? I know some people who, out of sheer boredom, buy things on Amazon at night that they don’t need. Everything is accessible, cheap, and you can always send it back. We have become lazier. What we completely ignore is that most of what fast fashion brings to the stores is made by people who don’t even have a minimum wage and can’t afford to live. 80 percent of a ten-euro T-shirt ends up in the brands’ pockets.

F: What was the key moment that influenced your shift to sustainable production?

EF : The first time I saw these huge warehouses in Italy with these unused treasures: unused fabrics, yarns, leather, buttons, sewing silk. But then I also experienced how an entire collection was destroyed because a small mistake was discovered. I didn’t know at the time that they would resort to such drastic methods, although they could certainly have found another solution. If you work for a large fashion house in a high position, you naturally get annoyed from time to time when the manager comes and says that you have to save money or that you don’t have a budget. But it was precisely this circumstance that led me to rethink how to solve problems and find solutions by rethinking the processes rather than resorting to cheaper materials and a lot of pre-production. This in no way means that you are limiting your own creativity, you are thinking in a rather complicated way, but differently and further.

F: What’s the greatest thing about being a designer, and what annoys you the most?

EF: It makes me happy to create something that brings joy to someone else. It’s great to have the opportunity not only to draw something, but also to make it yourself. It annoys me when customers want to negotiate the prices of my pieces for a unique item that has taken four to five days of work, was made from the best materials and costs 20 times less than a big brand that would produce the same piece at least a hundred times over. I detest this moment of justification and the moment when customers don’t buy the garment but a bargain and don’t even think about what’s behind it. If you sell yourself short, people will value you even less.

F: What preconception about the design profession annoys you?

EF: As a Russian living in Vienna, who only lived in Russia for the first five years of her life, the prejudice of the oligarch’s daughter accompanied me for a long time. People thought that only someone with a lot of money or connections could become a designer. I come from a family of hippie artists who had no money and worked very hard to get to where I am now. No amount of money in the world can buy all the experience and expertise I have.

F: Are fashion weeks like Fashion Week in Paris or Milan still in keeping with the times?

EF: I haven’t followed anything for years. When Phoebe Philo left Celine, I stopped watching the shows. In my opinion, a lot of labels have lost their identity, it’s largely become an ignorant circus.

F: Who is tipping the scales for the fashion industry to move in the right direction?

EF: It’s teamwork, no one person can do it alone. Sometimes I actually wonder whether it would make a difference if Kim Kardashian, for example, addressed all her followers and drew their attention to fast fashion. I believe that too many of us have no idea what is happening.

F: What do you want from fashion consumers?

EF: Consumers ultimately decide whether more or less needs to be produced. Our behavior towards the trend and the product is very important; the greater the demand and the more we consume, the more is produced and brought to market. During the pandemic, our behavior towards consumption has changed a lot, but I don’t know if this has had a long-term effect. At the moment, everything is exactly the same as before – and that’s very scary. You can get everything at any time of day, whether you need it or not. My wish would be for fashion consumers to support more young labels that work and produce sustainably and transparently. After all, they are the ones who will be responsible for the coming years. We must not forget that it is precisely these labels that are fighting for their existence and need customers much more urgently than fashion houses worth millions that work in the same way as they always have.

F: How has the role and social standing of designers changed in recent years?

EF: Fashion has become more political and open. There are more women at the top who are committed to issues such as feminism and emancipation as well as body, race, sex and orientation issues. It is very important that fashion has become more accessible and that, at the same time, discourses are taking place that were taboo ten years ago. The new generation of designers can build on this, but we urgently need solutions for the future, not more clothes and show.

F: Which item in your closet do you associate the most emotions with and why?

EF: I bought a pair of Vivienne Westwood men’s trousers in a store in Vienna 20 years ago. I worked in an ice cream parlor back then and spent almost my entire monthly wage on it. I wore the pants almost every day, and when they started to fall apart, I took off the pattern and re-sewed the pants in different fabric – but it was never the same. No matter what I did, I never got it right. In other words: I almost did what fast fashion companies normally do, but it was always just a copy and far removed from the original.

F: What do you have too much of and what do you have too little of?

EF: Too many ideas and only two hands.

F: How important are print fashion magazines to you?

EF: Very important. I see that my customers still read a lot of hard copy and don’t really place much value on social media. They are also women who take the time to read up on sustainability and fashion. The first impression is very important, because I am also telling a story with FATEEVA. You can’t get that across in an Instagram photo or an Instagram story, a Facebook post or a newsletter.

F: How do you envision the fashion industry in ten years?

EF: I hope that fashion will make sense again in ten years’ time.