Other journalists are typing their texts with their backs to the window. Maximilian Reich doesn’t. Our author types in places where nobody wants to go, where sheep outnumber people and road signs are rare. This time Reich reports from Nagarkot in Nepal.

A secret agent sits in front of me at her desk and looks deep into my eyes. “So you want to go to Nepal!”

There can be no question of wanting to. “My editor-in-chief makes me do it. I have to write a travel column about remote places,” I explain.

“Well, you have a nice boss,” says the spy. There’s a big sign on the office wall behind her that says: “Travel agency”. But of course she’s not fooling me. Everyone knows that travel agencies are actually front companies for secret service organizations. They wouldn’t be able to survive these days. Even my grandma books her coffee trips online. I wouldn’t be here either if my travel request wasn’t so specific. “Can’t you just eliminate it for me?” I ask hopefully. But the spy just laughs, as if I’ve made a joke. “That would probably be a bit of an exaggeration. But I’ve got just the thing for you. Have a look.” She turns her computer screen a little towards me and shows me pictures of a small town against an impressive mountain backdrop. “Nagarkot!” She says this as if it’s a secret parallel world behind a closet. “A small mountain village in Nepal with a fantastic view of the Himalayas.”

“And how do I get there?” I ask with a worried look. Nepalese airlines are the most dangerous airlines in the world. Crashes happen again and again. There’s no way I’m getting on one of those kamikaze planes.

The secret agent with the travel agent’s license takes a quick look at her computer. “Lufthansa or Emirates fly to Kathmandu several times a week. From there you can take a cab to Nagarkot.”

A relieved sigh escapes from my mouth. “All right.”

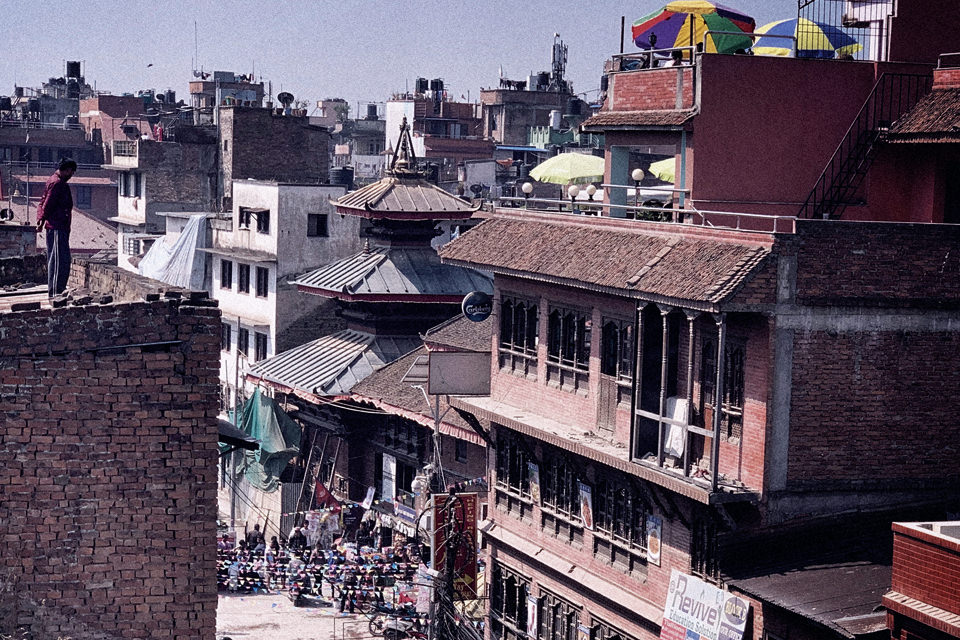

Five million people and one Max

Almost one million people live in Kathmandu. At least that’s what Wikipedia says. “Total nonsense,” says my cab driver. “It’s just under five million,” he clarifies as he maneuvers the car through the traffic with monk-like composure. Outside my passenger window, armies of scooters and rickety cars honk at each other. Pedestrians on the sidewalks wear masks against the smog that hangs over the city like a gray blanket. (Cities such as New York or Berlin, on the other hand, are like spas where you can catch your breath. Bad Berlin, so to speak). Along the roadside are shabby houses with unplastered facades from which yellowed advertising signs and power cables hang down. No, Kathmandu is not a beauty. A civil war raged in Nepal between 1996 and 2006. Many people fled from the countryside to the capital because it was safer here. There was a housing shortage and houses sprang up like pimples on a teenager’s mixed skin. “80 percent of the houses are built illegally,” explains my cab driver. The consequences of this were seen in the terrible earthquake in 2015, when 8,786 people died. The only exception is “Thamel”. The small district looks like a movie set. Narrow alleyways where the sunlight falls diagonally from above between the tall houses from which colorful prayer flags hang. Colorful carpet stores line up next to glittering jewelry stores, and the smell of perfume sticks hangs in every corner. But would I recommend the long flight? Rather not. Nevertheless, there may be a few know-it-alls who don’t want to be deterred – or who can no longer exchange their ticket . So here are a few tips: The best “Momos” can be found in the restaurant “Mo:Mo Star” in , a small side street of Thamel. Ten pieces of the traditional dumplings cost just 1 euro here. The best view over Kathmandu is from the “Monkey Temple”, and those who need a break from the hectic traffic can relax in the “Garden of Dreams”. A beautifully landscaped park in the middle of Thamel, surrounded by high walls that seal it off from the hustle and bustle. In the evening, you meet Europeans who want to climb Everest for a beer in “Sam’s Bar”. Incidentally, there is no Starbucks here – but the Nepalese chain “Java Himalaya Café” is practically the same. Well, that will have to do. Two days in Thamel are enough anyway. I only stay a third day because of the Holi festival, the Hindu spring festival that takes place every year in March. On the main squares there are jukeboxes or bands playing live, all the inhabitants come out of their houses onto the street and engage in the biggest color battle you can imagine. A kind of colored chalk is smeared on the face of everyone who passes by, and colorful dust flies through the air. There must be almost 2,000 people celebrating peacefully together in the center, the “Durbar Square” . I have never experienced such an exuberant atmosphere without alcohol. And despite all the criticism, I have to say one thing: I have rarely met such lovely people as the Nepalese. And apparently everyone wants to rub the white tourist with the colorful powder. As the crowd gradually disperses around 5 p.m. and I stroll back to the hotel, I look like Braveheart on Christopher Street Day.

No view of Everest

A bit of the stubborn paint is still sticking to my neck when I set off for Nagarkot the next morning. There are no bus connections, you have to take a cab for just under 25 euros . Now that we have finally managed to free ourselves from the traffic swamp of Kathmandu, there are fewer cars and fewer houses along the main road. Take a deep breath. The driver presses the accelerator and takes us through small villages and finally up a rugged mountain on a hairpin bend, where the colorless grass hangs down like the hair left on my grandmother’s mop of hair. Every few meters there is a dirty corrugated iron stand at the side of the road offering warm lemonade. Not a trace of tourists. I have to swallow. If something happens to me here, nobody will find me. I know places like this from movies: I’ll be kidnapped and my organs sold on the black market. If only I were a smoker. Or drinkers. That could perhaps save my life here. Those damn policemen back then in our 4B class with their stupid addiction prevention puppet show.

After two hours, a marketplace suddenly appears in front of us. It is no bigger than a football pitch, with rickety restaurants dotted around , from whose roofs the colorful prayer flags fly. It’s not pretty, but at least I have hope of getting out of here alive. My hotel is on the edge of the square. The small room is clean with a comfortable bed in the corner, but a bit cold. I check the air conditioning, but it’s switched off. I pull open the curtains to see if there might be a window open, but it’s closed. On this occasion, a small note: My hotel is called “Mount Everest Window View”. However, my window looks out onto a meadow no wider than a carpet. Behind it, trees obscure the view and a street dog poops on the meadow. But I guess “Dog Meadow Window View” didn’t attract that many visitors on Booking.com. Next I inspect the bathroom, and now I can see where the cold air is coming from. The window in the bathroom has no glass panes. Only a kind of blind hangs in front of it, but it cannot be closed even after several forceful attempts. Great. There is a water hose next to the toilet bowl. Of course. A million motorcycles rattle through the city center without an MOT, but then save on toilet paper because a water hose in the ass saves paper and is more environmentally friendly.

There is a knock. A small woman in traditional dress stands in front of my door and asks if everything is all right. Given her advanced age, she is less of a chambermaid and more of a chambermaid. She hardly speaks any English. She asks, “Are you all right?”

Me: “It’s a bit cold.” I point to the open bathroom. In many Nepalese accommodations there are no shower cubicles like in Western Europe. Instead, the entire room is tiled and a shower head hangs on the wall. That’s why you can’t enter the room in street shoes. But as I’m still wearing my leather boots and it would take an hour to untie the laces, I only point into the room from the outside. “Can you tell me how to close the window in the bathroom?”

The room grandma: “Cleaning?”

Me: “No, the window. How do you close it?”

The room grandma: “Okay, I’ll clean.”

Me: “No, no. Do not clean. Very clean. But cold. Close the windows.”

Well, anyway, she’s scrubbing the sink right now.

I don’t like it when other people clean up after me while I’m in the room. I’m too much of a gentleman. So I leave the room and explore the town for a while. However, there is not much to see. The small marketplace is actually everything. A hiking trail branches off from there, which is supposed to lead to a viewing tower from where you can see the Himalayas with its stars, Everest and Annapurna, as the travel spy had shown me on the computer. The hike leads up the mountain along a forest path. Again and again I have to take a breather, and locals who ride past on their motorcycles grin at me with encouragement. After an hour I finally reach the top and see: nothing. You would think that the largest mountain in the world would somehow stand out – but think again. Mount Everest is completely obscured by fog and clouds. If I hadn’t read it on the Internet beforehand – I wouldn’t know that I was just about to

Himalayas. It could just as well be the Black Forest. Disappointed, I trudge back again. After all, on the way back I pass the “Himalayan Club Resort”. A luxury hotel for wanderlusting tourists, where you can get the only cappuccino in the whole town. That’s another tip.

Just stay put

The next morning, my body still resents the fact that I did yesterday’s hike in my mid-height leather boots instead of hiking boots with ergonomic insoles, and is now punishing me with unbearable back pain. It feels as if a little man is squeezing my lower lumbar vertebrae with a pair of pliers like a walnut. I have to roll out of bed and only manage to sit up at all through gritted teeth. Putting on my shoes is out of the question. I spend 20 minutes trying to tie a boot, but as soon as I even bend forward to reach for the laces, the stupid little man squeezes his pliers even tighter and tears start to well up in my eyes. If I could at least make it to the bathroom. A hot shower might alleviate the discomfort. Suddenly there’s a knock at the door.

“Come in,” I groan.

The granny enters the room shyly with a cleaning bucket in her hand.

“They’re heaven sent,” I moan as I slump on the edge of my bed, helpless as a moronic pensioner on a chamber pot. “Could you perhaps help me stand up and support me into the bathroom?”

The room grandma lifts the cleaning bucket. “Cleaning the bathroom?”

Jesus Christ, she’s obsessed with cleaning the bathroom.

“NO! I need you to help me into the bathroom, please.”

“Okay,” she says and disappears into the bathroom with her bucket. I can hear the rubbing of her rag on the floor next door. Powerless, I let myself fall back onto the mattress. I just lie there until my flight home. I already have the conclusion of my text in my head: it’s dirty in Nepal. But the bathrooms are spotless.

Once again, our author Maximilian Reich sets off to explore the ass end of the world for us. It’s usually boring as hell there. That’s why he has a lot of time to write and has now published his new novel: “Reisemuffel an Bord” (Benevento Verlag, 16 euros).